Interview with Guillermo Fesser

"Children learn that they have Spanish roots and begin to appreciate and enjoy them"

September 2017. Reading time: 9 minutes

Spanish journalist and writer based in the United States. A former member of the legendary Gomaespuma Duo, Guillermo Fesser (Madrid, 1960) is the author of Get to know Bernardo de Gálvez, the only textbook in U.S. schools that makes mention of Spain's crucial help to Washington's army in achieving independence.

Simply put, who was Bernardo de Gálvez?

When the patriots of the 13 colonies declared their independence from England, two-thirds of what is now U.S. territory was a Spanish domain called New Spain. The capital was New Orleans, and its governor, during the war of independence, was Bernardo de Gálvez, from Malaga. Prior to that, Gálvez had captained the Dragones de Cuera (the Leather Dragoons): the first version of the Seventh Cavalry in Spanish western films. The Dragoons patrolled the royal road from Florida to California, defending settlers from attacks by Apaches and Comanches. They were called de cuera because of the seven-layer deerskin vest they wore as protection against arrows. Although the battle may seem very unequal today — the Indians with arrows and the cowboys with muskets — these firearms had to be loaded with gunpowder after each shot and in that one-minute interval the natives had time to shoot three arrows.

Is it true that without the help of the Hispanic army led by Bernardo de Gálvez, the United States would not have achieved independence in 1783?

When the patriots declared war on England and Scotland, they had a small problem: they had no army, no weapons and no means to manufacture them. They had no money to pay their soldiers, no factory to mint coins, no food for the troops — especially for the livestock that accompanied them which would devour it along the way —. Also, they did not have uniforms, blankets to keep warm or medicines to care for those wounded in the conflict. Additionally, they were surrounded.

By sea, help could not reach Washington because the Atlantic ports were blocked by the Royal Navy. To the north, the English controlled Canada. To the south they had Florida, which we had lost in the Seven Years' War. To the west, the Appalachian Mountains, with a host of indigenous tribes willing to fight European invaders, were impassable. The only possibility was help from neighbouring New Spain. New Orleans is at the mouth of the Mississippi River and Gálvez along this river and then along the Ohio River, sent thousands of blankets from Palencia and Zamora (both in Spain) and uniforms made in Soraluze (Guipúzcoa, Spain), thousands of muskets and hundreds of cannons, millions of Spanish dollars and tons of medicines — especially quinine from Peru to save the American army from malaria —.

How did you come up with the idea of writing a children's book about Bernardo de Gálvez?

Because I don't think the adults wanted to listen to my spiel. Today I tell them that the help from Spain was crucial and they say yes, yes, like the grandfather in My Big Fat Greek Wedding when he says that everything comes from Greece. In this country everyone sells their story. Today it's my turn and tomorrow, a German might tell them that the hamburger is theirs and after that, an Italian will claim that Columbus was an Italian but... in the end, it all remains the same. They still think Anglo-Americans are the best thing since sliced bread.

But children are different. Through my book Get to know Bernardo de Gálvez, which is already on the curriculum in many schools in the United States, the children learn in class that they have Spanish roots and begin to appreciate and enjoy them. By the time the 250th anniversary of the declaration of independence comes around, my students will have grown up with a different mentality, knowing that without the contribution of Spanish speakers, this country would not have become independent. From then on, perhaps Latinos will begin to occupy the positions of power that belong to us: we're 20% of the population, but we're being denied.

The book also tells the story of Teresa Valcarce. Is it true that this Spanish woman managed to get Bernardo de Gálvez's painting hung in the Capitol in 2014, during Barack Obama's term?

The book is actually the story of how Congress, upon achieving independence, promised to hang a picture of Gálvez in the Capitol as a tribute to Spain's contribution to their independence. But they never got around to doing it! The document, which proves the promise, found in Washington's national archives by Professor Manuel Olmedo, was published in the Diario Sur by the journalist Regina Sotorrío where Tere, a Spanish resident in Washington, read the article. The story was related to Senator Menendez, who had no idea, and he hung it in the Senate. Then Obama granted Bernardo de Gálvez honorary U.S. citizenship.

I have preferred to tell this story so that children feel closer to it and understand that to be a hero, you don't have to wear a white wig like Gálvez, that you can be an ordinary citizen like Tere to get justice.

What audience did you want to reach with this book, the Anglo-Saxon Americans or the Latin Americans and Spaniards living in the United States?

There are two versions of the book: the Spanish version, for reading in Spanish classes in bilingual elementary schools, and Get to Know Bernardo de Galvez, which is studied in history class in middle school. It is very important that Spaniards, Hispanics, Latinos, whatever they want to call us, know our own history and that feel proud of our contributions. But it is also important that those who do not speak Spanish know about it so that they understand that we did not arrive yesterday nor do we plan to leave tomorrow. That we have been here right from the beginning, our contribution has been crucial and that we belong to the United States as much as anyone else.

Children are not the biggest fans of talks, how did you get their attention and what was their response?

Actually, I don't go on about Gálvez, I explain how I created an illustrated book about Gálvez, so that they can create, if they want, their own illustrated book... or their own film, because in the end an illustrated book is a storyboard. I explain to them what happens if you place the camera too high or if you lower it, if you increase the light or if you record in darkness. I tell them that the skinny face that they can do to their mobile phone selfies was already done by painters hundreds of years ago in their portraits, when they cropped the nose of a king or increased the size of the pearls of a lady's necklace. I also show them the web we have created with the help of the Spain-United States Council Foundation, www.conocegalvez.com External link, opens in new window., where they can learn while enjoying a lot of games. And, along the way, I'm letting them know that without the army of free Africans, Native Americans, Spaniards and Creoles led by General Bernardo de Gálvez, Washington would still be trying to beat the English.

External link, opens in new window., where they can learn while enjoying a lot of games. And, along the way, I'm letting them know that without the army of free Africans, Native Americans, Spaniards and Creoles led by General Bernardo de Gálvez, Washington would still be trying to beat the English.

How did your collaboration with Iberdrola come about?

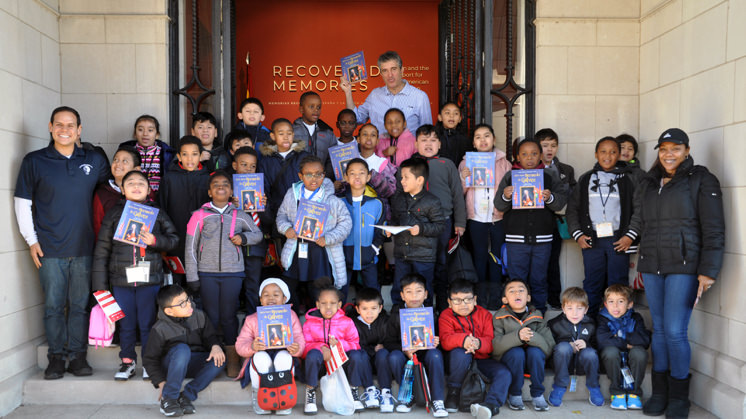

I've been living in New York for 10 years and, from there, I tell stories to Carlos Alsina in Onda Cero (a Spanish radio station) every Friday on the program More than One. I became curious when I found out that the exhibition Recovered Memories in New Orleans was going to be organised with the sponsorship of Iberdrola. The exhibition uncovered a part of the common history of Spain and the United States unknown to many people on both sides of the Atlantic. I interviewed and learned a lot of new things from the curator, José Manuel Guerrero. I was surprised that he had included my little book in the exhibition because it was the only textbook in US schools which explains the Spanish contribution to the Revolutionary War. From then on we were in contact and, when the exhibition moved to Washington, he asked me if I could contribute by giving talks to the schools that came to visit the exhibition. And here I am, getting a sound thrashing, but for a worthy cause. Every time a Latino student comes in troubled, feeling like a second-class citizen because of everything he hears, but then comes out of my presentation with his chest sticking out, I go to bed happy that night.

You have lived in the United States for many years, specifically in the state of New York. What is the opinion there of Spain?

Americans love Spain. It's sold. They speak only wonders about Spain and Spaniards. They like everything: the food, the climate, the history, the friendliness of the people... What confuses them is that when they go to buy the ticket, instead of one ticket office for Spain they find 27. One who says, "ah no, we only sell black pudding from Burgos"; another who says, "ah no, we are from Barcelona"; and another, "we only sell wine from Madrid". The famous Spanish Brand... We don't need any genius to come and invent it, because we Spaniards have invented it all by ourselves. What we need is to learn how to sell it together, instead of wasting time selling small pieces.

Do you have plans to continue promoting Hispanic culture in the United States?

I have a waiting list of schools from every corner of the United States map. My goal now is that the schools and teachers themselves are familiar with the website and can work through the curriculum in class without the need for my physical presence. I love to travel, but I can't be, like now, almost a month and a half without stepping foot in my house.

In any case, I have an idea for writing a new book telling the story of the Zamorano donkey, a Royal Gift, which King Charles III sent to Washington and which, after crossing it with a mare, is the origin of the famous American mules that today, for example, are the symbol of Kentucky bourbon and became a legend during the First World War.

Spanish Dollar

From the Spanish dollar to the US dollar.

Jai Alai

When Jai Alai made it big in the Americas.

'Recovered Memories' exhibition

Spain's forgotten contribution to American independence.

'Unveiling Memories'

Recovering a shared Hispanic and American history.